Imagine a world where a single cough could unleash a terrifying plague, dotting faces with disfiguring scars and leaving behind a trail of death that stretched across millennia. This was the reality for humanity, constantly shadowed by the specter of smallpox, a disease that had ravaged civilizations long before recorded history. Its invisible tendrils reached into every corner of the globe, leaving no community untouched, no era unscathed.

For centuries, smallpox was a relentless adversary. Early attempts at control were rudimentary, often relying on desperate measures like isolating the sick, a strategy that proved largely ineffective against such a pervasive enemy. The disease’s mortality rate was devastating, particularly among children, and those who survived were often left blind, their skin marred by the indelible marks of the pox. Its impact was not just physical; it was a constant source of fear, economic disruption, and social upheaval.

Then came a glimmer of hope, a scientific breakthrough that would alter the course of human history. In the late 18th century, English physician Edward Jenner observed that milkmaids who contracted cowpox, a milder disease, seemed immune to smallpox. This observation led him to a revolutionary experiment: inoculating an eight-year-old boy with material from a cowpox sore. The boy developed mild symptoms but recovered, and when later exposed to smallpox, he remained healthy. Jenner’s work laid the foundation for vaccination, a testament to keen observation and courageous experimentation.

However, vaccination was just the beginning. The real triumph, the complete vanquishing of smallpox from the face of the Earth, was a monumental feat of global public health orchestrated in the latter half of the 20th century. Spearheading this colossal effort was Dr. William Foege, a visionary epidemiologist whose strategic brilliance and unwavering dedication proved instrumental.

Foege understood that simply distributing vaccines wouldn’t be enough. Smallpox was a global scourge, and its eradication required a coordinated, systematic approach. His strategy, known as “ring vaccination,” was nothing short of ingenious. Instead of attempting to vaccinate entire populations, which was logistically impossible and financially prohibitive in many of the world’s poorest regions, Foege and his team focused on containing outbreaks. When a case of smallpox was reported, they would identify everyone who had come into contact with the infected individual – their family, neighbors, and anyone they had recently met. These individuals, the “ring” around the infected person, would then be rapidly vaccinated. The idea was to create a firewall, preventing the virus from spreading further.

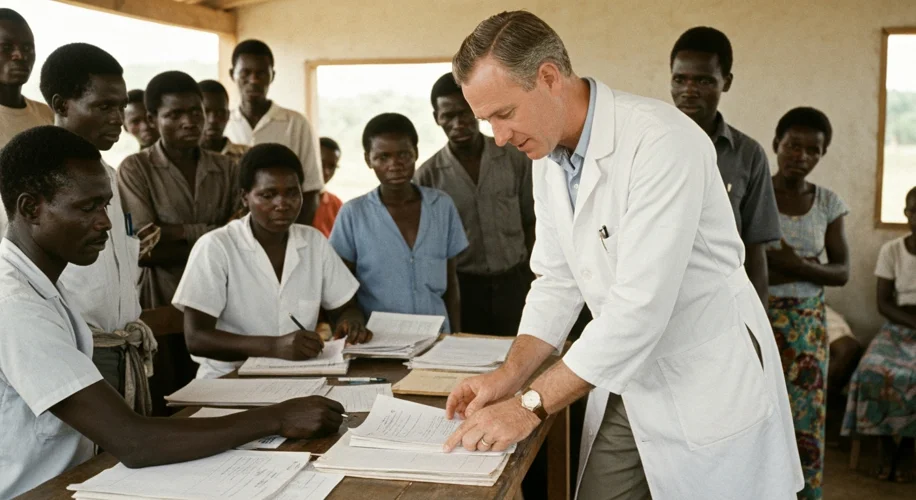

This strategy was particularly effective in countries with limited resources and challenging terrain. Imagine teams of dedicated health workers, often under harsh conditions, venturing into remote villages, armed with vaccines and an unyielding resolve. They faced not only the logistical hurdles of reaching isolated communities but also the skepticism and fear that often accompanied unfamiliar medical interventions. Yet, they persevered, driven by the belief that a smallpox-free world was achievable.

One pivotal moment in this global campaign occurred in Bangladesh in the early 1970s. Amidst the chaos of war and displacement, smallpox was rampant. Foege’s team, working with local health authorities, implemented the ring vaccination strategy with remarkable success. Their efforts not only helped control the epidemic in Bangladesh but also provided a crucial blueprint for future operations.

The World Health Organization (WHO), recognizing the potential of Foege’s approach, launched a global campaign in 1967 with the ambitious goal of eradicating smallpox. This was a bold undertaking, requiring unprecedented international cooperation. Nations, despite political differences and economic disparities, united under a common cause: to defeat a shared enemy.

Years of relentless effort followed. Health workers traversed continents, faced down dangers, and meticulously tracked down every suspected case. The process was painstaking, demanding immense patience and scientific rigor. Data collection was crucial; every reported case, every vaccination, was logged and analyzed to pinpoint the virus’s remaining strongholds.

The final chapter of this epic struggle was written in the late 1970s. The last naturally occurring case of smallpox was recorded in Somalia in 1977. Following this, intense surveillance efforts continued to ensure no new outbreaks emerged. And then, on May 8, 1980, the World Health Assembly officially declared smallpox eradicated. A disease that had haunted humanity for thousands of years was, at long last, gone.

The eradication of smallpox stands as one of public health’s greatest triumphs. It demonstrated the power of international collaboration, scientific innovation, and the unwavering dedication of individuals like Dr. William Foege. It saved countless lives and prevented immeasurable suffering. The estimated economic savings from eradication are staggering, allowing resources to be redirected to other critical health challenges. More importantly, it offered a profound lesson: that even the most formidable diseases can be defeated through collective will and concerted action. The world we live in today, free from the constant threat of smallpox, is a testament to this monumental achievement.