The year is 1956. The world, still reeling from the devastating Second World War, finds itself teetering on the brink of another global conflict, not over ideology this time, but over a vital strip of water.

The Suez Canal, a marvel of 19th-century engineering, was more than just a shortcut between the Mediterranean and the Red Seas. It was a symbol of empire, a lifeline for trade, and for newly ascendant nations like Egypt, a potent emblem of their reclaimed sovereignty.

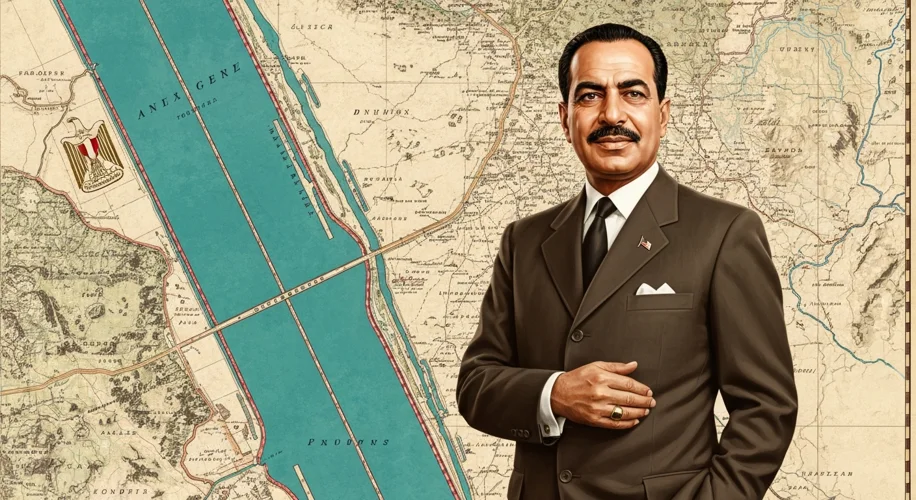

For decades, the canal had been under the control of the Suez Canal Company, a powerful entity dominated by British and French shareholders. This arrangement chafed under the skin of Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s charismatic president. Nasser, a fervent Arab nationalist, saw the canal as rightfully Egyptian, a symbol of his nation’s independence from colonial powers. He envisioned using its revenue to fund ambitious projects, most notably the Aswan High Dam, a monumental undertaking that promised to transform Egypt’s arid lands into fertile ground.

The stage was set for a dramatic confrontation. In July 1956, when the United States and Britain abruptly withdrew their financial backing for the Aswan Dam project, citing concerns over Egypt’s growing ties with the Soviet bloc, Nasser saw red. His response was swift and audacious. On July 26, 1956, Nasser stood before a roaring crowd in Alexandria and declared the nationalization of the Suez Canal Company. “We shall build the dam with our own money!” he vowed, his words echoing across Egypt and the Arab world.

This bold move sent shockwaves through London and Paris. For Britain, the canal represented a vital artery to its former empire, particularly to its oil supplies from the Middle East. For France, it was a matter of national pride and economic interest. Both nations, along with Israel, which felt threatened by Nasser’s rising regional influence and his country’s blockade of the Straits of Tiran, began to plot a response.

What followed was a carefully orchestrated, albeit clandestine, military operation. In late October 1956, Israel launched a lightning-fast invasion of Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. Under the guise of protecting the canal, British and French forces then issued an ultimatum to both sides to withdraw, a thinly veiled pretext to intervene militarily. As their paratroopers landed and gunboats shelled Egyptian positions, the world held its breath.

The invasion seemed, at first, to be a decisive success for the invading forces. However, international reaction was swift and overwhelmingly negative. The United States, under President Eisenhower, was furious. Not only had its allies acted without consulting Washington, but the crisis also threatened to push Arab nations further into the Soviet Union’s embrace. The Soviets, led by Nikita Khrushchev, also condemned the invasion, even issuing veiled threats of rocket attacks against London and Paris.

Facing immense diplomatic pressure from its most powerful ally and the looming threat of Soviet intervention, Britain and France were forced to back down. A ceasefire was brokered, and under the watchful eyes of a newly formed United Nations peacekeeping force, the invaders withdrew. The Suez Crisis, as it came to be known, was over.

But the consequences of this brief, intense conflict were far-reaching. For Britain and France, it marked a definitive end to their status as global superpowers. Their inability to act unilaterally, and their reliance on American approval, underscored their declining influence on the world stage. They were no longer the arbiters of international affairs.

For Gamal Abdel Nasser, the crisis was a resounding victory. Despite military defeat, his defiant stand against the old colonial powers cemented his image as a hero throughout the Arab world. His prestige soared, and his vision of Arab nationalism gained new momentum.

The Suez Crisis also highlighted the emerging bipolar world order dominated by the United States and the Soviet Union. It demonstrated that even traditional European allies could not defy American will without severe repercussions, and it solidified the Soviet Union’s role as a counterweight to Western influence in the Middle East.

Ultimately, the Suez Crisis of 1956 was a pivotal moment in post-war history. It irrevocably altered the geopolitical landscape, signaling the decline of European colonial powers and the rise of new nationalisms, while setting the stage for the Cold War’s complex global dance.