The name Robert E. Lee evokes a complex tapestry of American history – a revered general, a defender of the Confederacy, and a man inextricably linked to the institution of slavery. While often portrayed as a noble figure, a deeper examination of his life, particularly his stewardship of enslaved people, reveals a far more troubling narrative. The historical record, pieced together from letters, testimonies, and personal accounts, suggests that Lee’s relationship with slavery was not merely passive ownership, but one characterized by a severity that raises profound questions about his character and the moral compromises of his era.

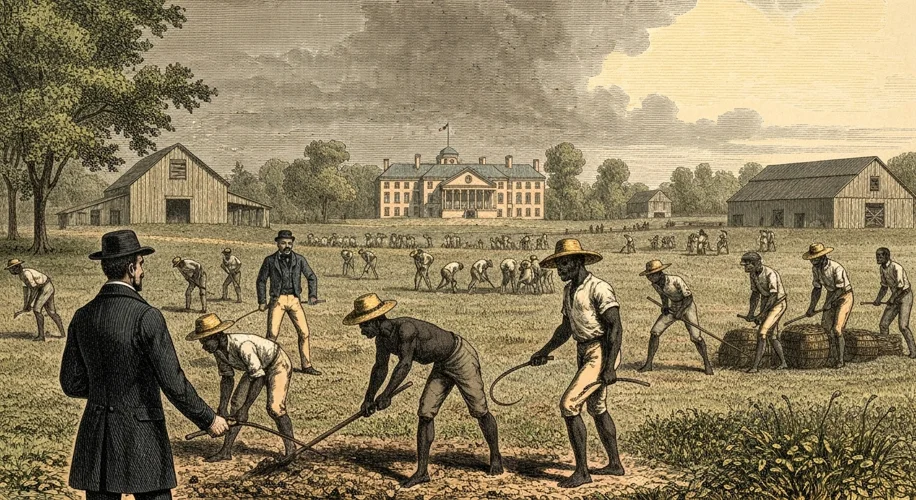

Born into privilege in 1807, Robert E. Lee inherited the mantle of slave ownership, a practice deeply embedded in the economic and social fabric of the antebellum South. His father, Henry Lee, a Revolutionary War hero, left significant debts, and it was through his wife, Mary Anna Custis Lee, a descendant of Martha Washington, that Robert gained control of the sprawling Arlington estate and its human chattel. The sheer scale of his wife’s inheritance—over 150 enslaved individuals—meant Lee was not a casual owner but a manager of human beings, responsible for their labor, their welfare, and their perceived obedience.

Accounts from those who lived under Lee’s direct command, both white and Black, offer a stark contrast to the idealized image often presented. Among the most compelling testimonies comes from Lee’s own household and plantation records, as well as the recollections of formerly enslaved individuals who sought freedom. One such account comes from a man named Wesley Norris, who as a boy was enslaved at Arlington. Norris, along with other enslaved individuals, recounted instances of brutal punishment, including the use of the lash, administered for perceived infractions. Norris’s testimony, given years later, described Lee as a man who would whip slaves “for the smallest thing” and that his wife, Mary Anna, was “very mean” to them.

While proponents of Lee’s legacy often dismiss such accounts as the biased recollections of individuals seeking retribution or compensation, the consistency across multiple testimonies and the documentation of Lee’s own efforts to sell off or break up enslaved families present a more disturbing pattern. In 1859, following a period where many of the enslaved people under his management had attempted to escape, Lee took drastic action. He made the decision to sell off several members of the Custis family’s enslaved population, including Eleanor, who was sold away from her husband, and a young woman named Ann Maria, who was sold with her infant child. These sales, particularly the separation of families, were common cruelties of slavery, but when enacted by a figure like Lee, they underscore the harsh realities of his management.

Lee’s own writings offer little solace. While he publicly espoused a paternalistic view of slavery, believing it to be a benevolent institution that civilized Africans, his private correspondence reveals a more pragmatic, and perhaps colder, approach. He viewed enslaved people as property, as assets to be managed and disciplined. In letters to his wife, he spoke of the “troublesome” nature of some of the enslaved individuals and the need for “firmness” in their management. This language, coupled with the documented sale of human beings, paints a picture of a man who, while perhaps not reveling in cruelty, was certainly willing to employ its tools to maintain order and control over his human property.

The legacy of Robert E. Lee is a potent reminder of the moral complexities and inherent cruelties of the antebellum South. The historical evidence, including the testimonies of those he enslaved and his own documented actions, challenges the notion of a benevolent slaveholder. Instead, it suggests a man who, within the brutal framework of slavery, managed his human property with a severity that inflicted pain, suffering, and the profound indignity of family separation. The debate over Lee’s character cannot ignore the voices of the enslaved, whose experiences offer a stark and essential counterpoint to the romanticized narratives of the past, forcing us to confront the uncomfortable truth that even the most revered historical figures were often complicit in, and perpetrators of, profound human suffering.

Timeline of Key Events:

- 1807: Robert E. Lee is born.

- 1831: Lee marries Mary Anna Custis, inheriting the Arlington estate and its enslaved population.

- 1859: Lee sells several enslaved individuals, including members of families, from the Arlington plantation.

- 1861-1865: Lee commands the Army of Northern Virginia during the Civil War.

- 1870: Robert E. Lee dies.