In the annals of ancient history, few civilizations have left as indelible a mark on the world’s maritime landscape and cultural exchange as the Phoenicians. Often shrouded in the mists of time, these enigmatic people, originating from the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, were the true pioneers of their age. Their story is not one of grand empires built on conquest, but of resilient city-states, intrepid mariners, and ingenious traders who charted unknown waters and connected disparate cultures.

Before delving into their remarkable achievements, it’s crucial to understand the cradle of their civilization. The Phoenicians hailed from the fertile crescent, a region encompassing modern-day Lebanon, parts of Syria, and northern Israel. This land, blessed with cedar forests and access to the sea, fostered a unique cultural identity. Their society was organized into independent city-states, the most prominent being Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos. Unlike their land-based neighbors who often sought territorial expansion through warfare, the Phoenicians turned their gaze seaward. Their religion was polytheistic, with deities like Baal and Astarte playing central roles, and their societal structure was deeply influenced by trade and maritime success.

The historical context for the Phoenicians’ rise is one of dynamic change and opportunity. Emerging in the Late Bronze Age (circa 1550-1200 BCE) and flourishing through the Iron Age (circa 1200-300 BCE), they navigated a world where great powers like Egypt, the Hittites, and later the Assyrians, Babylonians, and Persians often vied for dominance. The collapse of the Bronze Age, which led to widespread disruption and the decline of many established powers, paradoxically created a vacuum that the Phoenicians, with their adaptable and outward-looking nature, were perfectly positioned to fill. The sea, a barrier to many, became their highway.

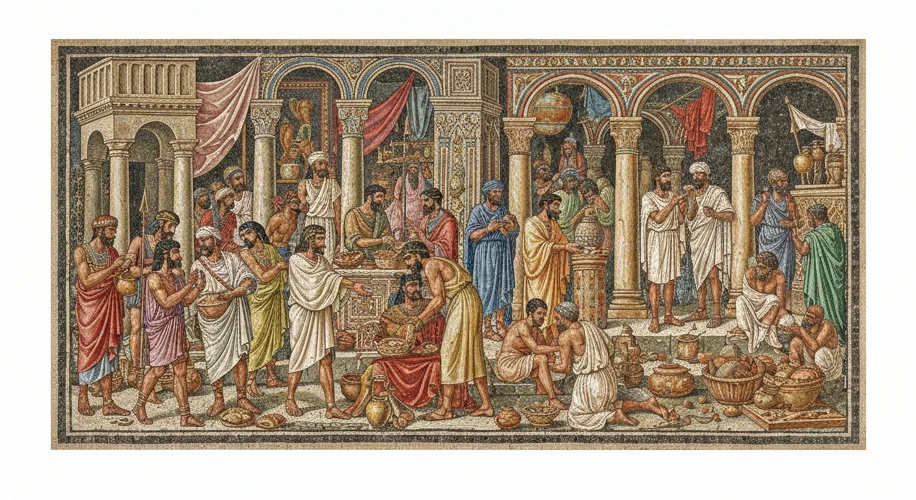

Central to the Phoenician identity were their roles as master shipbuilders, navigators, and merchants. Imagine a bustling harbor like Tyre around 1000 BCE. The air would be thick with the scent of salt, tar, and exotic spices. The rhythmic clang of hammers on wood would echo as sturdy, broad-beamed ships were constructed, designed for both cargo and long-distance voyages. Their vessels, famously equipped with sails and oars, allowed them to traverse the Mediterranean with an unprecedented reach.

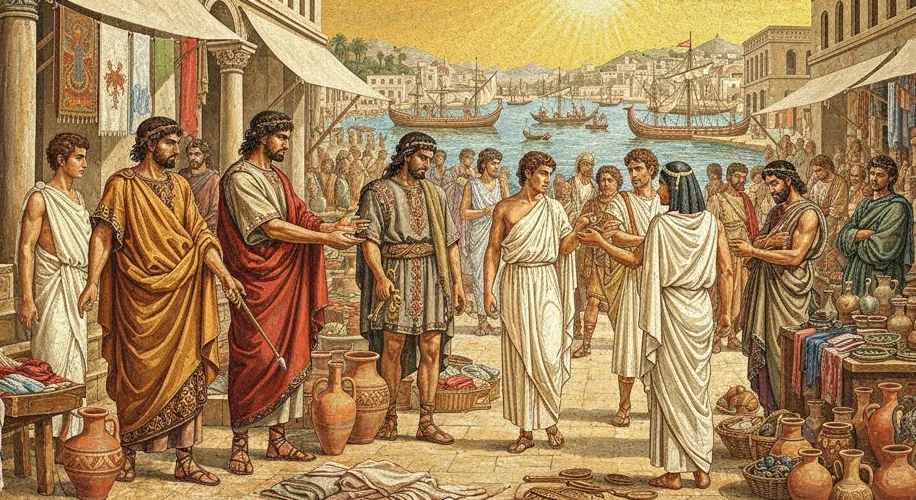

Their trade network was vast, extending from their homeland across the Mediterranean to Cyprus, Crete, mainland Greece, North Africa, Sicily, Sardinia, Spain, and even beyond the Strait of Gibraltar to the Atlantic coast. They exported cedar wood, famous for its durability and fragrance, glass (they were pioneers in glassmaking), fine textiles dyed with the precious Tyrian purple (extracted from murex shells, a process that gave them their name – ‘Phoenician’ derives from the Greek word ‘phoinix’, meaning ‘purple’), metalwork, and wine. In return, they imported raw materials like tin from Britain, silver from Spain, and grain from Egypt.

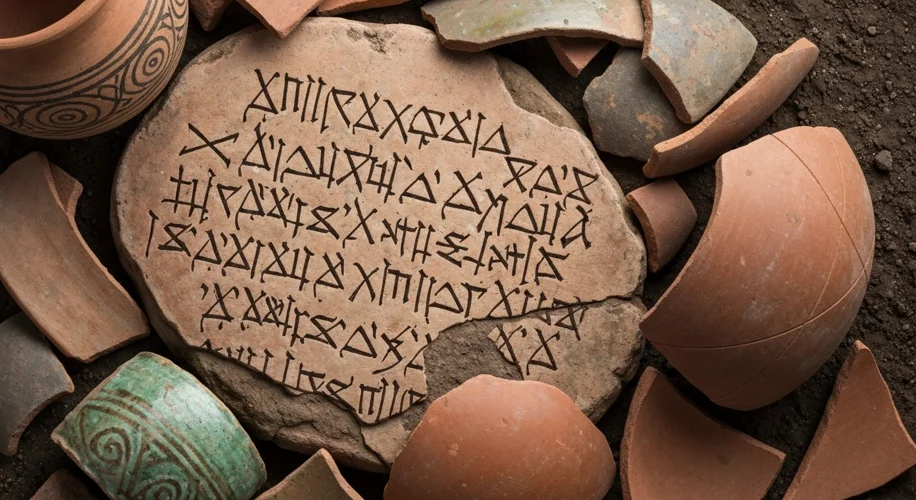

But the Phoenicians were more than just traders; they were cultural conduits. Their interactions with diverse peoples facilitated the exchange of ideas, technologies, and artistic motifs. Perhaps their most enduring contribution, however, was the development of the alphabet. Building upon earlier Semitic scripts, the Phoenicians created a simplified, phonetic alphabet of 22 consonants. This elegant system, easily learned and adaptable, was disseminated throughout the Mediterranean world. The Greeks adopted and modified it, adding vowels, laying the foundation for the Latin alphabet that underpins many modern European languages. It was a revolutionary leap in communication, democratizing literacy and enabling the spread of knowledge like never before.

The impact of the Phoenicians cannot be overstated. Their seafaring expertise pushed the boundaries of the known world. Legends speak of their circumnavigation of Africa, a feat credited to an expedition sponsored by the Egyptian Pharaoh Necho II around 600 BCE. Their colonies, such as Carthage in North Africa, grew into powerful city-states in their own right, eventually challenging the might of Rome.

Despite their profound influence, pinpointing a singular ‘Phoenician identity’ can be complex. They were a confederation of closely related city-states, each with its own nuances. Furthermore, as they established colonies, especially in the western Mediterranean, these settlements developed distinct cultural characteristics. The Carthaginians, for instance, while retaining strong Phoenician roots, evolved into a formidable maritime power with unique customs and governance.

The story of the Phoenicians is a testament to the power of innovation, trade, and cultural exchange. They were the quiet architects of much of the ancient world’s interconnectedness, their legacy woven into the very fabric of alphabets, seafaring, and global commerce. They remind us that history is not only written by conquerors but also by the persistent, resourceful spirit of traders who dared to sail beyond the horizon.