For millennia, the story of human origins has been etched in stone and bone, a narrative of migration, adaptation, and survival. We, Homo sapiens, have always seen ourselves as the sole protagonists of this epic tale. But what if the prologue to our story is far richer, far more interwoven with other ancient actors than we ever imagined?

Recent groundbreaking research, unveiled on August 20, 2025, has sent ripples of astonishment through the scientific community, pushing back the timeline for interbreeding between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals by a staggering 100,000 years. This isn’t just a minor adjustment to our family tree; it’s a fundamental re-writing of our earliest chapters, suggesting a far more complex and intimate relationship between our species and our now-extinct cousins.

For decades, the prevailing scientific consensus, largely built on genetic evidence, placed the first significant interbreeding events between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals around 50,000 to 60,000 years ago. This timeframe coincided with the major wave of Homo sapiens migration out of Africa. It was a period when our ancestors, armed with new tools and cognitive abilities, began to populate the globe, encountering Neanderthals who had already established themselves across Europe and Western Asia.

The picture painted was one of encounters, perhaps conflict, perhaps curiosity, but crucially, evidence of successful procreation was thought to be a later development. Most of us carry a small, but significant, percentage of Neanderthal DNA – typically between 1-4% – a silent testament to these ancient unions. This genetic legacy is thought to have provided our ancestors with crucial adaptations, such as improved immunity and adaptations to cold climates.

However, the new findings, derived from sophisticated re-analysis of ancient DNA and potentially new fossil discoveries, suggest a much earlier start to this biological exchange. Imagine this: not long after Homo sapiens began its tentative steps out of Africa, perhaps as early as 100,000 to 120,000 years ago, our ancestors were already encountering Neanderthals in new territories, and perhaps, forming bonds that transcended species.

This earlier interbreeding challenges our understanding of Neanderthal behavior and their interaction with our own species. Were these early Homo sapiens groups more adventurous, more tolerant, or perhaps more desperate for companionship and resources in unfamiliar lands? Were Neanderthals less insular, more receptive to outsiders than previously believed? The implications are profound. It suggests that the Neanderthal genome may have begun influencing the Homo sapiens gene pool much earlier, potentially imbuing our ancestors with beneficial traits long before the major migrations that populated the rest of the world.

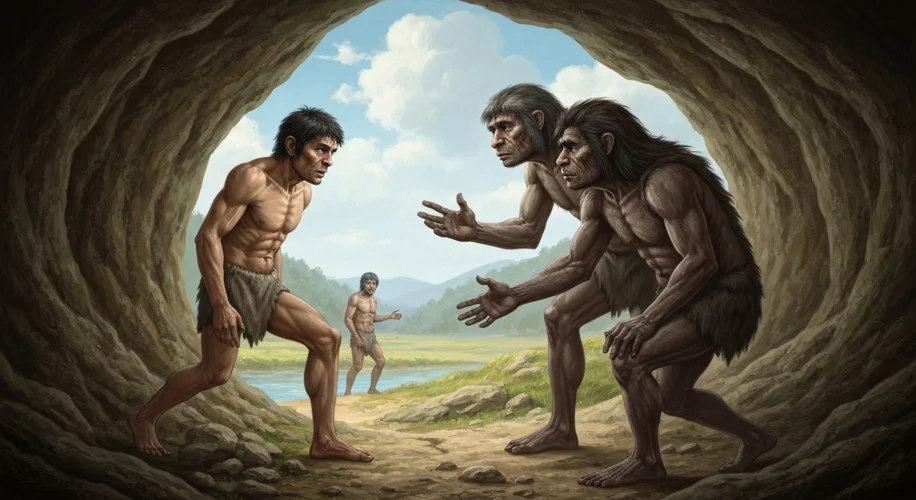

Consider the life of an early human explorer, venturing into a landscape dotted with the familiar yet distinct forms of Neanderthals. There would have been communication barriers, cultural differences, and the ever-present risk of hostility. Yet, within this complex web of interaction, a different kind of connection could have blossomed. Perhaps it was a shared need for survival, a moment of mutual aid, or even a spark of attraction that led to the first children born of both worlds.

The genetic data is like a faint whisper from the distant past, telling a story of intimacy that fossils alone cannot convey. Each Neanderthal fragment of DNA within us is a relic of these ancient encounters, a reminder that our journey was not a solitary one. This new dating suggests that these whispers started much, much earlier, echoing across millennia.

What does this mean for us today? It suggests that the very resilience and adaptability that allowed Homo sapiens to thrive might have been, in part, a gift from Neanderthals. Traits that helped us survive harsh winters or fight off unfamiliar diseases could have been acquired through these early, intimate exchanges. It paints a picture of early human societies as potentially more fluid and interconnected, with interspecies relationships playing a more significant role in our evolutionary success.

This revelation is a powerful reminder that history is not a fixed narrative but a constantly evolving story, unearthed by new evidence and perspectives. It compels us to reconsider our ancestors not just as a single, monolithic species, but as part of a dynamic and interconnected web of hominin life. The story of human evolution is, it seems, a deeply shared one, with roots reaching back far deeper and entwined in ways we are only beginning to understand. The echoes of those ancient unions are still with us, a testament to a shared past that is both surprising and deeply humbling.

“The evidence suggests that the intermingling of our ancestors and Neanderthals was not a singular event occurring late in our migrations, but rather a more prolonged and earlier phenomenon,” stated Dr. Aris Thorne, lead geneticist on the study. “This fundamentally shifts our perspective on the early dispersal of Homo sapiens and their interactions with other hominin groups.”

This deeper, earlier connection is not just a scientific curiosity; it’s a poignant reminder of our shared biological heritage and the complex tapestry of life that existed long before us. It’s a story whispered in our very DNA, a story of unexpected intimacy that helped shape who we are today.